Asia Central, región geoestratégica

Ex: http://elordenmundial.com

Muchas veces la división del territorio mundial en continentes no es suficiente para realizar estudios detallados de ciertas zonas del Planeta. Por eso, el mundo se divide en varias regiones o subregiones, aceptadas y diferenciadas por la Organización de las Naciones Unidas (ONU).

Una de estas regiones del mundo es la zona de Asia Central. Localizada entre el Mar Caspio y la frontera oeste de China, esta región, antiguamente conocida como el Turkestán, está formada actualmente por cinco repúblicas ex-soviéticas: Kazajistán, Kirguizistán, Tayikistán, Turkmenistán y Uzbekistán.

Geografía física

Al norte de Irán, Afganistán y Pakistán se encuentran los países del Asia Central, una extensa región de más de 4 millones de kilómetros cuadrados. Los “Cinco -stán” se pueden dividir en dos grupos: los llanos y los montañosos. Mientras que Kazajistán, Uzbekistán y Turkmenistán son extensas llanuras, Kirguizistán y Tayikistán son dos pequeños países montañosos.

Los tres primeros países tienen una superficie mucho mayor y deben su planitud a la gran Meseta de Ustyurt, de 200.000 kilómetros cuadrados. En esta zona el clima es árido y el suelo rocoso, siendo la altitud media de 150m. Tradicionalmente, la población de los alrededor de Ustyurt se ha dedicado a actividades relacionadas con el pastoreo, con rebaños de cabras, ovejas y camellos, sin llegar a asentarse definitivamente en ningún lugar.

Por otro lado, Kirguizistán y Tayikistán, mucho más pequeños, son dos países rodeados por importantes cordilleras montañosas. En el caso de Kirguizistán, el escudo del esta ex-república soviética simboliza el relieve que predomina en el país. Es en ocasiones llamado la “Suiza de Asia Central”, debido a que la región montañosa de Tian Shan cubre el 80% del territorio.

Por otro lado, Kirguizistán y Tayikistán, mucho más pequeños, son dos países rodeados por importantes cordilleras montañosas. En el caso de Kirguizistán, el escudo del esta ex-república soviética simboliza el relieve que predomina en el país. Es en ocasiones llamado la “Suiza de Asia Central”, debido a que la región montañosa de Tian Shan cubre el 80% del territorio.

Tayikistán no es menos montañoso, ya que a las montañas del Tian Shan se une la cordillera del Pamir, lo cual hace que más del 50% de la superficie de este país se encuentre por encima de los 3.000 metros.

Las cordilleras de Tian Shan y del Pamir son dos de los relieves más importantes del mundo, junto con los Himalayas, las Montañas Rocosas y los Andes. Esta región del mundo está bajo la influencia de grandes relieves montañosos, lo cual hace que Asia Central sea un lugar inhóspito y de difícil acceso.

Aun así, en Kirguizistán y Tayikistán encontramos también tierras bajas y valles, donde se encuentran la mayoría de ciudades y donde se concentra la actividad económica. En en el noroeste de Tayikistán se encuentra el Valle de Ferghana, la zona más fértil de todo Asia Central.

La región de Asia Central es atravesada por dos importantes ríos: el Syr Darya por el norte y el Amu Darya por el sur.

La región de Asia Central es atravesada por dos importantes ríos: el Syr Darya por el norte y el Amu Darya por el sur.

El río Syr Darya nace en las montañas de Tian Shan, mientras que el Amu Darya nace en la Cordillera del Pamir. Ambos llegan hasta el Mar de Aral y suponen la principal fuente de agua de la región.

El clima de Asia Central está marcado por una continentalidad extrema, que limita las posibilidades de explotación de la tierra y de asentamiento de la población. Con excepción de algunas zonas, como el ya mencionado Valle de Ferghana (compartido por Uzbekistán, Kirguizistán y Tayikistán) con una tierra fértil, una buena provisión de agua y un alta densidad de población.

El resto de Asia Central se distingue por paisajes desérticos, desde el desierto de arena de Turkmenistán que forma parte de la depresión aralo-caspiana, hasta las herbosas estepas de Kazajstán que anticipan Mongolia, y por paisajes montañosos, como los que ofrecen las cordilleras Pamir y Tian-Shan, cadenas montañosas al norte del Himalaya.

El desierto de Karakum cubre el 80% del territorio de Turkmenistán, y el desierto de Kyzylkum una gran parte de Uzbekistán. Por otro lado, y como ya hemos dicho, el 41% de la superficie de Kirguistán y casi la mitad de la territorio de Tayikistán se encuentran a una altitud de más de 3.000 m. (fuente: casaasia.es)

fuente del mapa: stantours.com

Geografía económica: ¿dónde se localizan los recursos?

Con casi 65 millones de habitantes, Asia Central es una región muy poco poblada. La densidad de población es de 16 habitantes por kilómetro cuadrado. Las ciudades más importantes son Almatý (1.400.000 hab.), Astaná (700.000 hab.), Taskent (2.100.000 hab.), Biskek (800.00 hab.) y Asjabad (1.000.000 hab.). Otras, como Dushanbe (Tayikistán) muestran este fantasmagórico aspecto.

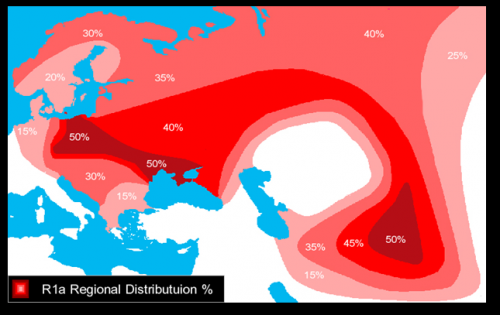

Al contrario que otras regiones como el Sudeste Asiático, que están superpobladas, la zona de Asia Central se ha caracterizado siempre, desde los tiempos de la Ruta de la Seda, por ser una región despoblada y utilizada principalmente como de paso.

Al contrario que otras regiones como el Sudeste Asiático, que están superpobladas, la zona de Asia Central se ha caracterizado siempre, desde los tiempos de la Ruta de la Seda, por ser una región despoblada y utilizada principalmente como de paso.

La vida en la estepa y entre las montañas no es fácil. La mayoría de la población ha sido siempre nómada (en el dibujo de la izquierda, casas kirguizas fácilmente desmontables).

Las pocas ciudades grandes actuales, sin embargo, sí que representan centros de relativa importancia económica. Astaná se presenta como una ciudad moderna que puede llegar a ser un importante centro financiero y de negocios, líder de la región.

La población de esta región se concentra en dos zonas principalmente: el norte de Kazajstán (zona de la capital, Astaná) y el Valle de Ferghana (confluencia de Uzbekistán, Tayikistán y Kirguizistán). El Valle de Ferghana es la zona más fértil de la región de Asia Central, y allí la gente se ha podido asentar gracias a los cultivos de arroz, patatas y algodón.

Pero aunque la agricultura es la base de la economía real para las gentes que viven en el Valle de Ferghana, en esas tierras existen recursos mucho más importantes que los agrícolas. Es una zona rica en petróleo, gas y minas de jade.

En Asia Central, aunque la mayoría de la población siga subsistiendo de la actividad pastoril y agrícola, los gobiernos han comprendido que el crecimiento económico y el desarrollo se basan en su capacidad para exportar materias primas. En otras palabras, con un rebaño de cabras uno puede vivir, pero con un yacimiento de gas uno puede hacerse millonario.

Por eso mismo los gobiernos de Asia Central quieren desmarcarse de la tradicional imagen de nómadas y agricultores, para pasar a ser potenciales exportadores de importancia mundial.

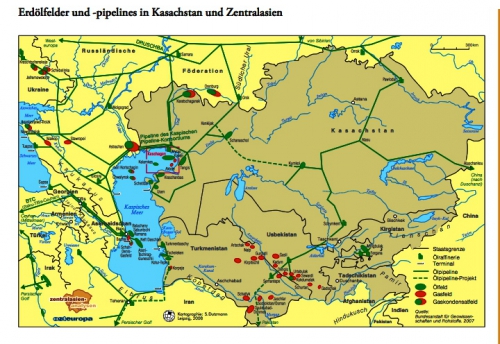

En relación al petróleo y el gas, son los países más cercanos al Mar Caspio los que se benefician de los yacimientos. Las reservas de petróleo de Asia Central se estiman en 50.000 millones de barriles. Kazajstán tiene el 3,2% de las reservas petrolíferas del mundo, y Turkmenistán el 8,7% de las reservas de gas.

TABLA: Países por reservas probadas de gas natural (Wikipedia)

TABLA: Países por reservas probadas de petróleo (Wikipedia)

Pero no sólo es importante el hecho de tener materias primas, sino también tener la posibilidad de moverlas y exportarlas. Y los países de Asia Central están sabiendo hacerlo. Por ejemplo, en Kazajstán, los importantes yacimientos de Kashagan (petróleo) y Karachaganak (gas), están conectados mediante oleoductos y gasoductos con Rusia, a través del Caspian Pipeline Consortium, un consorcio entre varias empresas privadas y públicas para la gestión de dicha ruta entre Kazajstán y Rusia. En 2008 se movilizaron 35 millones de toneladas de petróleo.

En el siguiente epígrafe analizaremos las distintas rutas que siguen oleoductos y gasoductos desde Asia Central hacia el resto del continente.

Las potencias tradicionales (Reino Unido, Francia, Alemania, Estados Unidos…) están dejando paso a las potencias regionales en el control de los recursos de Asia Central. De esta forma, los gobiernos ruso y chino, junto a los de Kazajstán, Turkmenistán y Uzbekistán, están realizando el reparto de los yacimientos en el entorno del Mar Caspio. De forma que son los países de la región los que explotan y exportan las materias.

NOTICIA: La inglesa BP vende a la rusa Lukoil su participación en el yacimiento kazako de Tenguiz

Por otro lado, a parte de gas y petróleo, la zona de Asia Central es rica en recursos minerales. Como vimos en el artículo Minerales codiciados, Kazajistán es un país emergente en la exportación de estas materias primas. Dispone del 30% de las reservas mundiales de mineral de cromo, el 25% del manganeso y el 10% del hierro. Además, Kazajstán es el tercer productor mundial de titanio y el mayor productor de uranio del mundo.

INTERESANTE: El uranio en Kazajstán: Industria atómica (Invest in Kazahstán)

En el siguiente documento (hacer click aquí) el gobierno de Uzbekistán hace una llamada a inversores japoneses para que se adentren en la industria de la minería. El documento (una presentación powerpoint) es toda una publicidad del país, que se ofrece como gran socio comercial y como un lugar perfecto para desarrollar proyectos empresariales.

De la misma forma, Kirguizistán está realizando una reforma de la industria minera y en el año 2012 concedió más de 500 licencias a empresas para explotar sus recursos mineros.

NOTICIA: Kirguizistán promueve la reforma de la industria minera (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Gobierno de España)

Todos estos recursos naturales suponen grandes oportunidades de negocio en Asia Central. La riqueza que ha llegado a países como Kazajstán al convertirse en exportadores de materias primas ha permitido que se desarrollen todo tipo de proyectos punteros y modernos.

También se puede observar el progreso y la modernización en fotos de la ciudad de Astaná, una ciudad que está siendo construida de nuevo, con arquitectura futurista gracias al dinero obtenido por la exportación de gas, petróleo y minerales.

Gracias a este redescubrimiento de Asia Central, han aparecido nuevas empresas que se localizan allí y realizan no sólo tareas de explotación de recursos, sino que se adentran en el sector terciario y algunas han aparecido como empresas de servicios, como la del siguiente caso:

INTERESANTE: La empresa Manuchar se encarga de asistir a los fabricantes de materias primas del Este a comercializar sus productos en Occidente, al mismo tiempo que ayuda a los fabricantes orientales a conseguir los materiales necesarios para poder desarrollar su actividad empresarial. Es una empresa que ofrece servicios desde el principio hasta el final de cada transacción e informa sobre las tendencias de mercado en la zona en cuestión. (web: www.manuchar.com)

Como hemos dicho, los de Asia Central son países que se han dado cuenta de la riqueza que tienen bajo su tierra, y están encantados con el libre comercio y la economía de mercado que predominan en el mundo. Tienen la oportunidad de establecer importantes lazos comerciales y no van a desaprovechar la oportunidad. Como muestra, esta carta redactada por el Ministerio de Petróleo, Gas y Recursos Minerales de Turkmenistán: abrir pdf aquí. Dice textualmente: “The aim of this event is to provide the Asian business community with a better insight into the wealth of investment opportunities available in Turkmenistan’s oil and gas sector, and to both reinforce and establish new business relationships between Turkmenistan and other countries.” Es decir, que el gobierno de Turkmenistán ofrece a empresas de otros países a que acudan a invertir en el sector del petróleo y del gas.

Fotografía: vista de Astaná, la moderna capital de Kazajstán

Fotografía: vista de Astaná, la moderna capital de Kazajstán

Posición geoestratégica en el conjunto de Eurasia

Recogiendo el testigo de la época de la Ruta de la Seda, cuando el Turkestán era una importante zona de paso que comunicaba Europa con China, actualmente Asia Central sigue siendo un punto geoestratégico por su localización en el conjunto del continente euroasiático. Pero no sólo es una cuestión geográfica, sino también económica, ya que Asia Central se redescubrió en el S.XX como una prominente región en cuanto a las materias primas.

Como hemos visto en el anterior subapartado sobre Geografía Económica, bajo el suelo de Asia Central se encuentran millones de metros cúbicos de gas y petróleo, así como innumerables recursos minerales. Pero lo que vamos a analizar ahora es la ventaja de la localización geográfica.

Eduardo Olier, en su libro Geoeconomía: las claves de la economía global (2012), resume el contexto geoestratégico de Asia Central de la siguiente manera:

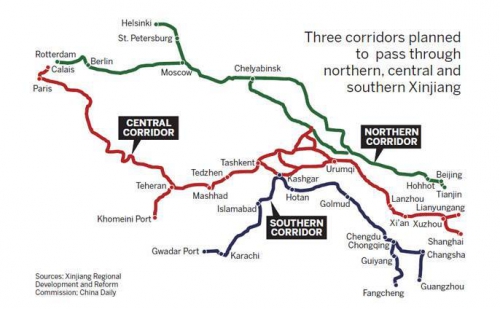

“En este complejo escenario, las rutas energéticas del área se presentan como un elemento geoeconómico esencial. Primero, hacia el Norte, favoreciendo a Rusia. En segundo lugar, hacia el Oeste, ruta pretendida por Azerbaiyán que favorece los intereses de Estados Unidos, Turquía e, incluso, Georgia, para facilitar el tráfico con Europa. Tercero, la ruta Sur, más viable económicamente que, sin embargo, pone a Irán en el eje estratégico y por lo tanto dificulta los intereses americanos. Cuarto, la ruta Este hacia China, una costosísima infraestructura que sólo en Kazajstán deberá atravesar 2000 kilómetros. Y, finalmente, la posibilidad de atravesar Afganistán por el Sudeste para llegar a Pakistán y la India. Un complejo escenario de intereses geopolíticos que convertirá esta zona en una de las más sensibles del planeta en los próximos años.”

Al ser una zona de paso y que conecta los mundos Occidental y Oriental, Asia Central está repleta de puntos estratégicos. La mayoría de ellos son pasos o corredores entre las montañas, que permiten llegar desde las llanuras de Asia Central hasta países importantes como Pakistán, China o India, donde el desenfrenado crecimiento económico requiere abastecerse de las materias primas que los países de Asia Central les pueden proveer.

Los principales pasos que conectan Asia Central

El Paso de Torugart, en las montañas Tian Shan, une la Provincia de Naryn (Kirguizistán) con la enorme región de Xinjiang, la más grande de China. Es un paso importante porque constituye la ruta principal para conectar los países de Asia Central con China.

Otra localización importante es el Paso de Khunjerab, un alto paso de montaña a 4.700m, en la cordillera del Karakorum, estratégicamente situado en la frontera norte de Pakistán con China. Es el cruce internacional de frontera pavimentada más alto en el mundo, además de ser el punto más alto de la famosa carretera del Karakorum, que une la ciudad de Kashgar (China) con Islamabad (capital pakistaní).

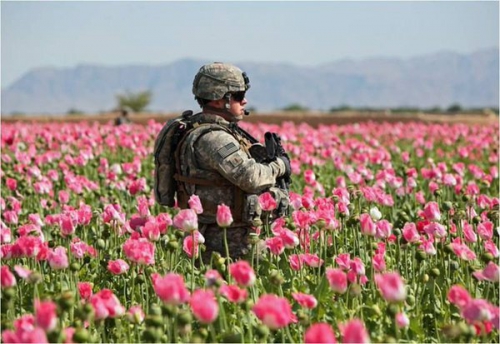

El norte de Afghanistán, que también se puede incluir en la región geográfica de Asia Central, es una zona de importancia geoestratégica, ya que este país está, desde 2001, ocupado por tropas estadounidenses y de otros países. Afghanistán es un país en guerra.

El norte de Afghanistán, que también se puede incluir en la región geográfica de Asia Central, es una zona de importancia geoestratégica, ya que este país está, desde 2001, ocupado por tropas estadounidenses y de otros países. Afghanistán es un país en guerra.

Aunque las principales campañas militares se están desarrollando en el sur y en el este del país, controlar los pasos fronterizos del norte es un objetivo estratégico.

En la fotografía de la derecha se puede observar un tanque, símbolo de la presencia militar en la zona, y al fondo la gran cordillera del Hindu Kush, que domina la mitad norte de Afghanistán.

El Corredor de Wakhan es uno de los lugares geoestratégicos más importantes de Asia Central. Situado al noreste de Afghanistán, se encuentra en la Cordillera del Pamir, haciendo frontera con Tayikistán al norte, China al este y Pakistán al sur. Este corredor fue abierto por el Imperio Británico a finales del S.XIX para impedir que Rusia llegara a la India durante el Gran Juego.

También entre Afghanistán y Pakistán se encuentra el importante Paso de Khyber, uno de los pasos más antiguos de la historia, que ya era utilizado en la época de la Ruta de la Seda. Situado en la parte noroeste de las montañas Safēd Kōh, es una ruta comercial entre Asia Central y el Subcontinente Indio, además de una localización militar estratégica.

Geoestrategia energética: petróleo y gas

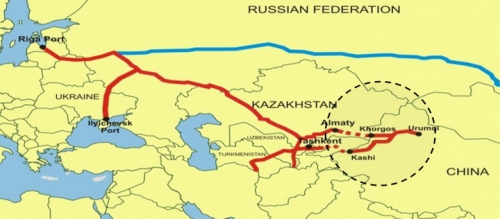

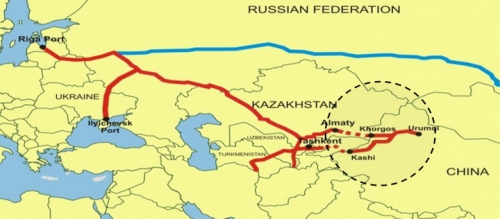

En el mapa Asia Central: una posición geoestratégica se observa de manera simplificada las cuatro direcciones principales que siguen las exportaciones desde Asia Central. Aunque hay importantes socios comerciales en Europa, el Golfo Pérsico y la India, el mayor receptor de minerales, gas y petróleo está siendo el gigante asiático, China.

Las proyecciones indican que en un futuro más cercano que lejano China consumirá 7 millones de barriles de petróleo al día. Necesitará abastecerse no sólo de Arabia Saudí y de Irán. Asia Central es y será cada vez más un socio exportador para China.

En esta región, las reservas de petróleo y gas suelen estar en el entorno del Mar Caspio, de forma que los pequeños Kirguizistán y Tayikistán no se benefician de estos recursos. Desde Asia Central parten varios oleoductos y gasoductos en todas direcciones.

En esta región, las reservas de petróleo y gas suelen estar en el entorno del Mar Caspio, de forma que los pequeños Kirguizistán y Tayikistán no se benefician de estos recursos. Desde Asia Central parten varios oleoductos y gasoductos en todas direcciones.

Por ejemplo en 2005 se inauguró un oleoducto de 1000km entre las ciudades de Atasu (Kazajstán) y Alashankou (China).

Otro oleoducto une los campos petrolíferos de Tenguiz (Kazajstán) con el puerto ruso de Novorosslysk, através del Mar Negro.

También existen gasoductos que unen los yacimientos de la costa este del Mar Caspio con el Mar Mediterráneo, a través de Rusia, Azerbaiján y Turquía.

Esto pone de manifiesto que, aunque no tengan salida al mar y estén situados en zonas remotas, los países de Asia Central se mantienen vivos y activos en el mercado internacional de exportaciones debido a las buenas comunicaciones que se han desarrollado gracias a la inversión de países poderosos como China o Rusia, que ayudan a que las materias primas consigan llegar desde Asia Central hasta Europa, la India y China.

MUY INTERESANTE: Las rutas del petróleo en Asia Central (Real Instituto Elcano)

Además del petróleo, el otro recurso que se mueve a través de tuberías por las llanuras de Asia Central, en todas direcciones, es el importantísimo gas natural, muy presente entre los yacimientos que rodean el Mar Caspio.

INTERESANTE: KazMunayGas, empresa kazaka dedicada a la exportación de gas desde Kazajstán hacia Rusia y China principalmente.

La India también está interesada en Asia Central, tal y como muestra el proyecto Trans-Afghanistan Pipeline (TAP), que supondrá un enorme gasoducto que unirá los yacimientos del Mar Caspio con Pakistán y la India, a través de Turkmenistán y Afghanistán.

El proyecto TAP podría transportar 30.000 millones de metros cúbicos de gas al año, una cantidad muy importante. Este gas sería utilizado por los superpoblados y emergentes Pakistán e India, dos países que consumen cada vez más recursos.

El proyecto TAP podría transportar 30.000 millones de metros cúbicos de gas al año, una cantidad muy importante. Este gas sería utilizado por los superpoblados y emergentes Pakistán e India, dos países que consumen cada vez más recursos.

El gasoducto trans-afghano transportará gas desde el yacimiento de Dauletabad, en Turkmenistán, hasta la ciudad india de Fazilka, en el estado de Punjab (30 millones de habitantes). Un recorrido de casi 1700km.

INTERESANTE: Turkmenistán-Afghanistán-Pakistán-India Gas Pipeline: South Asia’s Key Project

Desde el yacimiento de Dauletabad en Turkmenistán también parten otros importantes gasoductos en otras direcciones, como por ejemplo el Dauletabad-Sarakhs-Khangiran Pipeline, inaugurado en 2010, que llega hasta la ciudad de Khangiran, en Irán. Este gasoducto transporta 12.000 millones de metros cúbicos de gas cada año.

En los últimos años, Turkmenistán, poseedor del 8,7% de las reservas de gas del mundo, ha comprometido toda su exportación con tres países: Rusia, China e Irán, lo cual supone una derrota de las potencias occidentales (Estados Unidos y Europa). En la guerra geoestratégica por los recursos, se puede decir que la “batalla de Asia Central” la está ganando el bloque oriental.

Con China realizando inversiones multimillonarias y con Irán cerrando pactos con países como Turkmenistán, queda por analizar qué movimientos está realizando Rusia.

La empresa rusa Gazprom, líder mundial en la extracción y distribución de gas, no ha tardado en ocupar una posición privilegiada en la zona de Asia Central. Actualmente controla un sistema de gasoductos que van desde Turkmenistán hasta Rusia, pasando por Uzbekistán y Kazajstán.

Esta red de gasoductos controlada por Gazprom se alimenta de los campos de gas del sudeste de Turkmenistán y de los yacimientos de la costa este del Mar Caspio. Además de llegar hasta Rusia, está planeado que los gasoductos lleguen un día hasta China.

MÁS INFORMACIÓN: Central Asia-Center gas pipeline system (Wikipedia)

Los expertos en Asia Central, Marlène Laruelle y Sébastien Peyrouse, resumen la situación de esta manera: “Se trata de países rentistas que funcionan principalmente gracias a la exportación de materias primas (petróleo, gas, algodón, uranio, oro, minerales raros…) y a la importación de productos manufacturados, principalmente de China, pero también de Europa. Situados entre Rusia, China e Irán tienen dificultades para encontrar su lugar en el contexto de la economía mundial, y se ven frenados en su globalización por un entorno geopolítico inestable y una fuerte caída del capital humano.”

MUY INTERESANTE: Asia Central en el contexto de la economía mundial

Mapa superior: principales gasoductos y oleoductos de la región (fuente: realinstitutoelcano.org)

Las principales potencias mundiales y su relación con Asia Central

EEUU y Europa han extendido la OTAN hacia el este europeo incluyendo antiguas “democracias populares” y repúblicas soviéticas. La expansión hacia el oriente no ha parado ahí y, a partir de 2002, la OTAN ha creado los Planes de Acción de Asociación Individual (Individual Partnership Action Plans) con otras antiguas repúblicas soviéticas como Georgia, Azerbaiján, Armenia, Kazajstán y Moldavia. Por último, en el marco de la invasión de Afganistán, EEUU consiguió establecer bases militares en Kirguizistán y Uzbekistán. El mundo occidental ha movido sus piezas en una zona controlada por la URSS durante la guerra fría. (Fuente: www.historiasiglo20.org)

Como respuesta a estos movimientos de las potencias occidentales, la presencia de China en Asia Central ha aumentado considerablemente en los últimos años, lo cual ha generado ciertos recelos hacia el gigante asiático por parte de Kazajstán y Kirguizistán, que temen sobre sus posibles aspiraciones hegemónicas.

China está extendiendo su influencia económica a lo largo de su frontera de 2.800 kilómetros con Asia Central para compensar la presencia estadounidense y rusa, en una región con enormes reservas minerales y de recursos energéticos, como ya hemos visto.

NOTICIA: China expandirá su presencia en Asia Central con una inversión de $10.000 millones (Reuters)

En Asia Central se han desarrollado importantes organizaciones intergubernamentales, como la Organización de Cooperación de Shangai (OCS), una de las iniciativas de cooperación regional más prometedoras de Asia. Esta organización incluye a China, Rusia, Kirguizistán, Tayikistán y Uzbekistán. Además, otros socios son Pakistán, Irán, Mongolia e India (estos últimos tienen un estatus de observadores).

China lidera la OCS y, por tanto, las cuestiones energéticas y comerciales de la región están muy influenciadas por los intereses chinos. No es de extrañar, pues, que la mayoría de los nuevos oleoductos y gasoductos estén proyectados en dirección este, hacia territorio chino.

Aunque en la declaración fundacional de la Organización de Cooperación de Shanghai se afirma que no es una alianza hecha contra otras naciones o regiones, la mayor parte de los analistas coinciden en que uno de los objetivos principales de la OCS es hacer de contrapeso a la OTAN y a EEUU.

INTERESANTE: Página web oficial de la Organización de Cooperación de Shanghai

Además de la Organización de Cooperación de Shanghai (OCS), otros proyectos intergubernamentales se están poniendo en marcha. Por ejemplo, en 2012 el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores de la India habló de que su país iba a comenzar una política de conexión con Asia Central, con el objetivo de reforzar las relaciones políticas y económicas con países como Kazajstán o Turkmenistán, así como apoyar a las tropas internacionales en el conflicto armado de Afghanistán.

Una de las bases para la cooperación entre India y Asia Central tendrá que ver con el intercambio de materias primas por tecnología y equipamientos médicos. La India es un país puntero en los campos de la tecnología y la medicina, y Asia Central, como hemos visto, es una tierra rica en recursos naturales. La cooperación y el entendimiento entre países se apoyará en las necesidades de cada parte, para construir una importante relación comercial y política.

INTERESANTE: La importancia de Asia Central

Presencia militar en la zona de Asia Central

Estados Unidos tiene bases aéreas desplegadas por toda la región: en Uzbekistán, Kiguizistán, Tayikistán, Pakistán y, cómo no, en Afghanistán. Con Rusia vigilando desde el norte, China apretando desde el Este, e Irán atento en el Sur, la zona que rodea al Mar Caspio se convierte en un tablero de ajedrez en el que cada movimiento genera tensión en el contrincante. Hay muchos recursos en juego.

Estados Unidos tiene bases aéreas desplegadas por toda la región: en Uzbekistán, Kiguizistán, Tayikistán, Pakistán y, cómo no, en Afghanistán. Con Rusia vigilando desde el norte, China apretando desde el Este, e Irán atento en el Sur, la zona que rodea al Mar Caspio se convierte en un tablero de ajedrez en el que cada movimiento genera tensión en el contrincante. Hay muchos recursos en juego.

En la infografía de la derecha podemos ver una clara relación entre yacimientos petrolíferos y presencia militar. Es una zona donde convergen los intereses de las potencias tradicionales (Occidente) y las nuevas potencias emergentes (países asiáticos como India, China, Irán o Pakistán).

VER MAPA: Inestabilidad en Oriente

En Kirguizistán, Estados Unidos tiene la base de Manás, a pocos kilómetros de la capital, Bishkek. Esta base tiene el objetivo geoestratégico de vigilar la inestable zona de Afghanistán.

Por su parte Rusia también quiere mantener su influencia en la zona. Tiene en Kazajistán una base de lanzamientos espaciales en Baikonur, y está construyendo otra base de lanzamiento en Baiterek. También tiene bases en Kirguizistán y en Tayikistán.

Pero tanto Estados Unidos como Rusia están perdiendo esta guerra geoestratégica ante el poder de China, que, mediante la Organización de Shanghai, promueve sus intereses y recorta territorio a sus vecinos Tayikistán y Kirguizistán, obligándoles a firmar nuevos tratados fronterizos. China, con el poder del dinero, ha conseguido lo que Estados Unidos y Rusia no han podido con el poder militar.

NOTICIA: EEUU busca crear su mayor base militar en Asia Central (RT.es)

NOTICIA: Rusia toma medidas para no perder más terreno en Asia Central (elpais.com)

Gustavo Sierra, escribiendo para el diario argentino Clarín, hace este interesante resumen de la situación en Asia Central: (fuente: Clarín.com)

Asia Central fue escenario del “Gran Juego” que practicaron Rusia y Gran Bretaña en el siglo XIX. Ahora, vuelve a ser el terreno de una disputa aún más grande de la que participan no sólo los antiguos contrincantes sino Estados Unidos, China, In dia y las otras grandes potencias europeas.

En el centro de la disputa están las inmensas reservas petroleras y gasíferas de la región. Y para obtener ventaja en “el juego” las potencias aumentan su presencia militar en todo centroasia. En el aeropuerto de Dushanbé, la capital de Tayikistán, se puede ver una escuadrilla de modernos bombarderos franceses. No muy lejos de ahí, los ingenieros indios reconstruyen una enorme pista soviética. Los rusos mantienen aún en ese valle rodeado por las míticas montañas del Panshir una unidad de 10.000 soldados. En la vecina Kirgyzstán, sobrevuelan los KC-135 estadounidenses, los Sukhoi-27 rusos de la base cercana de Kant, y los bombarderos chinos.

Y las repúblicas “stán” (todos sus nombres tienen esa terminación) reciben presiones de todos lados. Kazajstán debe decidir si continúa sacando su petróleo por la red de oleoductos rusa o si se conecta con la nueva línea Baku-Ceyhan, recientemente construida con el apoyo de EE.UU. China compró una de las petroleras más grandes de ese país y construyó un oleoducto de 2.000 kilómetros para transportar el fluido a Beijing.

Claro que la región es un polvorín donde no para de crecer el radicalismo islámico. En particular en el valle de Fergana que cruza las fronteras de Uzbekistán, Tajikistán y Kirgyzstán. Allí es poderoso el movimiento de Hizb ut-Tahrir, que forma parte de Al Qaeda.

Pero las potencias cuando necesitan de algo o alguien no tienen reparos.Y para continuar recibiendo gas y petróleo al tiempo que mantienen a raya al radicalismo islámico, siguen apoyando a los regímenes autoritarios de la zona, desde el tadyico, Imomali Rakhmon, hasta el brutal kazako, Nursultan Nazarbayev. (fuente: Clarín.com)

MUY INTERESANTE: Geopolítica petrolera en Asia Central y en la cuenca del Mar Caspio

Fotografía: panorámica de las montañas Tian-Shan

Fotografía: panorámica de las montañas Tian-Shan

Si te gusta nuestra web puedes ayudarnos a crecer con una pequeña donación a través de:

Autor y Director de la web 'El Orden Mundial en el S.XXI'. Graduado en Geografía por la Universidad de Zaragoza y Máster en Relaciones Internacionales Seguridad y Desarrollo por la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Inquieto por comprender cómo funciona el mundo y apasionado de la divulgación de conocimiento. Además de blogger, soy un viajero incansable.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

The very mention of the Silk Roads creates an instant image: camel caravans trudging through the high plains and deserts of central Asia, carrying silks, spices and philosophies to Europe and the larger Mediterranean. And while these ancient routes may remain embedded in our imagination, they have, over the past few centuries, slowly faded in

The very mention of the Silk Roads creates an instant image: camel caravans trudging through the high plains and deserts of central Asia, carrying silks, spices and philosophies to Europe and the larger Mediterranean. And while these ancient routes may remain embedded in our imagination, they have, over the past few centuries, slowly faded in

Du point de vue économique et géopolitique, ce sera, dans tous les sens du terme, un rival au canal de Suez. Selon un article publié par Sputnik International de Russie, le projet a été approuvé en 2012 par l’ancien Président iranien Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, au moment où les sanctions occidentales étaient toujours en place. Le coût avait été estimé alors par Khatam-al Anbiya, une société d’ingénierie appartenant à la Garde révolutionnaire iranienne, à environ sept milliards de dollars. À cette époque, dans une démarche visant à bloquer le projet, Washington avait imposé des sanctions économiques aux entreprises qui participaient au projet. Maintenant, pour d’autres raisons géopolitiques, Washington a levé de nombreuses sanctions et Téhéran

Du point de vue économique et géopolitique, ce sera, dans tous les sens du terme, un rival au canal de Suez. Selon un article publié par Sputnik International de Russie, le projet a été approuvé en 2012 par l’ancien Président iranien Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, au moment où les sanctions occidentales étaient toujours en place. Le coût avait été estimé alors par Khatam-al Anbiya, une société d’ingénierie appartenant à la Garde révolutionnaire iranienne, à environ sept milliards de dollars. À cette époque, dans une démarche visant à bloquer le projet, Washington avait imposé des sanctions économiques aux entreprises qui participaient au projet. Maintenant, pour d’autres raisons géopolitiques, Washington a levé de nombreuses sanctions et Téhéran

Seymour Hersh, chroniqueur diplomatique et politique réputé, souvent accueilli dans la London Review of Books, vient de publier un article

Seymour Hersh, chroniqueur diplomatique et politique réputé, souvent accueilli dans la London Review of Books, vient de publier un article